How did Company X get a 9 digit valuation in 2 years?

Recently, I was part of a Mentor for Hope panel to answer the audience’s questions around the fundraising process beyond Series A. The title above was one of the questions that came out, click on the link above to find out what the panelists have to say about that.

Source: DilbertA sense of bewilderment, frustration, curiosity was mixed within the audience’s questions, some of which I will like to share below:

How do VCs value companies that are loss making?

Do unit economics only matter at Series B?

Can you raise Series A with a proof of concept?

How important is the team Pre-Series A vs Post Series A?

How much does key-man risk impact fundraising?

The consensus from the panel is that VC valuations are more of a product of the negotiation process (or art) rather than science. To sum it up in one line and to remind the audience of who VCs are:

VCs value you at the point where they can both get into your round and “expect” to make money on exit down the road

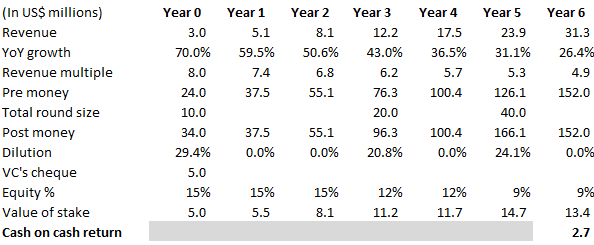

Simply put, if a VC writes a cheque for US$10 million at a revenue multiple of 8x, they expect to at least 3x that US$10 million net of dilutions from future rounds and decreases in revenue multiple as the company approaches a liquidity event.

To illustrate, see below for an example with arbitrary numbers.

And this is how the VC’s cash on cash returns are impacted by revenue growth rates and exit multiples.

If a VC’s targeted return is at least 3x, you will need to convince the investor that your revenue growth rates are sustainable while maintaining sound contribution margins so that your revenue multiple does not get compressed.

As a company gets closer and closer to late stage, revenue multiples start to normalise towards public valuations. In the public markets, a rule of thumb is companies with lower contribution margins and/ or high fixed cost structures get lower revenue multiples.

An unintended side effect of high revenue multiples for early stage funding

Raising early stage funding at high revenue multiple implies that management is under the hook to maintain high revenue growth rates in order to maintain its attractiveness for future fund raises. If revenue growth is sustained by burning cash for market share, then it all depends on the attractiveness of the space and whether there have been precedents of peer companies crashing and burning. If there are, such as in the case for co-working, revenue multiples will undergo a huge compression across the space. Companies who have raised at high multiples in the past are then caught in a catch 22 where they cannot raise without a down round to continue fueling their bloated unit cost structures.

Moral of the story is to be clear on why you are fund raising and what you will use the funds for. Also be very clear on your company’s levers for both growth and profitability and to not over-reach no matter how tempting it is when liquidity is sloshing.

The valuation of your company is but a number and is no way a validation of yourself and your business. Building a solid business, rallying like-minded people around a purpose that you are passionate about to create value is the most important goal.

Let’s be clear about that.